Coordinating the Corridors

S. Frederick Starr

March 20, 2025

This article was originally delivered as a speech in March 2025 at an Asian Development Bank conference on connectivity and trade under their Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program.

Read Coordinating the Corridors (PDF)

The New Russia-Iran Treaty: Implications for the South Caucasus Region

By Sergey Sukhankin

Weakened by economic sanctions and bearing significant consequences for their geopolitical endeavors, Iran and Russia have solidified their post-2022 partnership, elevating it to the status of a comprehensive strategic partnership. The imperative to secure their borders and mitigate the impact of economic sanctions positions the South Caucasus and certain areas of the Caspian Sea as the focal points for deepening cooperation between Tehran and Moscow. Among the smaller regional actors, Azerbaijan is likely a primary beneficiary due to its geographically strategic location. Simultaneously, Russia may be inclined to reclaim some of its regional influence. This prospect is both precarious and potentially destabilizing for the region, as Russia’s historical engagement in the area has been characterized by conflict and disruptive interventions.

BACKGROUND: On January 17, Russia and Iran signed a Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, marking the first high-level agreement between the two nations since 2001. Although historically characterized by tension and complexity, bilateral relations have undergone a significant transformation after 2022, in light of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and its resulting international isolation. This period has seen a rapid elevation of Russian-Iranian ties, with some experts even suggesting the formation of an Entente.

The primary impetus behind this strengthening of relations lies in the challenges faced by both states. Politically isolated and subjected to extensive sanctions, Russia has become embroiled in a protracted and costly war. With limited strategic alternatives, Russian leadership has increasingly aligned itself with authoritarian regimes and internationally marginalized states—such as North Korea and Belarus—in an effort to mitigate the effects of its diplomatic and economic isolation and to secure critical military support.

Iran’s situation is arguably even more precarious. In addition to ongoing economic struggles and internal social unrest, Iran experienced a series of significant geopolitical setbacks between 2023 and 2024. At the end of 2024, the Tehran-backed regime of Bashar al-Assad was overthrown by the Turkish-supported opposition. Furthermore, the Israel-Hamas war inflicted severe damage on another of Iran’s key Middle Eastern proxies. These developments have reportedly exacerbated internal divisions within the Iranian political establishment, leading segments of Iran’s military-political elite to adopt a more critical stance toward Moscow.

Despite these disagreements, Russia and Iran remain compelled to act as close partners—if not outright allies—in the domains of defense and security, and perhaps even more so in trade and economic cooperation, as both seek to mitigate the detrimental effects of international sanctions. In this context, collaboration in the Caspian Sea region—particularly in specific areas of the South Caucasus—is expected to play a pivotal role in reinforcing Russo-Iranian ties.

IMPLICATIONS: The strengthening ties between Russia and Iran are expected to have a significant impact on the geo-economic landscape. As emphasized by Russian President Vladimir Putin, "the essence of the Treaty [between Russia and Iran] is about creating additional conditions [...] for the development of trade and economic ties. We need less bureaucracy and more action." This objective is explicitly outlined in Clause 13 of the Treaty.

At present, economic and trade cooperation between Tehran and Moscow remains limited. In 2024, the reported trade volume between the two countries did not exceed US$ 4 billion. However, this may change in the future, primarily due to Russia’s evolving geopolitical strategy. Given its significantly weakened global position after 2022, Moscow increasingly views Iran as its “window to Asia”—a crucial conduit for circumventing Western-imposed economic sanctions and mitigating their severe economic impact.

In pursuit of this objective, Russo-Iranian cooperation is expected to strengthen in two key domains. First, there will likely be an intensification of trade along the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)—a 7,200-kilometer multimodal freight route encompassing ship, rail, and road networks that connects India, Iran, Azerbaijan, Russia, and Central Asia. The INSTC is increasingly regarded as a viable alternative to traditional maritime trade routes such as the Suez Canal and the Bosphorus Strait.

Within this framework, Azerbaijan stands to be a primary beneficiary, as its strategic geographic position between Iran and Russia will elevate its role as a crucial transportation hub, significantly enhancing its economic and geopolitical importance within the region.

Azerbaijan’s role could be further reinforced if the two countries proceed with the construction of a natural gas pipeline through Azerbaijani territory. Initially agreed upon in 2022 and reaffirmed in late 2024, this project represents a significant expansion of regional energy cooperation. In his most recent statement on January 17, 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that the proposed pipeline would have a capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas—equivalent to the Nord Stream 1 capacity—and could potentially be extended to Pakistan and even India.

However, some Russian experts question the economic viability of the project, arguing that its feasibility remains uncertain. They suggest that the pipeline could serve as a political instrument for Russia to exert pressure on China, possibly as a means of persuading Beijing to strengthen its energy ties with Moscow. Nevertheless, if both the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and the gas pipeline are successfully implemented, the South Caucasus—and Azerbaijan in particular—will see a marked increase in geopolitical and economic significance as a critical Eurasian transportation and energy corridor.

Although defense and security are not the primary focus of the Russo-Iranian Treaty, as explicitly stated by Iran’s Ambassador to Russia, Kazem Jalali, certain shifts in the regional security landscape are nonetheless anticipated.

One key factor influencing these dynamics is the aftermath of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War (2020), resulting in an undisputed victory for Azerbaijan which not only received strong backing from Turkey but also enjoyed tacit Russian support. This outcome significantly weakened Iran’s position in the South Caucasus, while simultaneously bolstering its strategic adversary, Turkey. In addition to consolidating its influence over Azerbaijan, Turkey also strengthened economic, political, and energy ties with both Azerbaijan and Georgia, marking a substantial geopolitical success for Ankara and further diminishing Tehran’s leverage in the region.

However, in the post-2022 period, the geopolitical landscape of the South Caucasus has undergone further transformations, creating additional common ground for Russo-Iranian cooperation. The increasing prominence of Turkey, which directly contradicts the strategic interests of both Russia and Iran, has been a key factor in this shift.

Simultaneously, Russia’s influence over both Armenia and Azerbaijan has weakened. Armenia’s signing of a Charter on Strategic Partnership with the U.S. implies a diversification of its geopolitical partnerships, potentially reducing Moscow’s leverage in Yerevan.

Moreover, by the end of 2024, anti-Russian sentiment became more pronounced in Abkhazia, a breakaway region that has been heavily reliant on Moscow. These developments have raised alarms among Russian analysts, some of whom have warned of Russia’s "approaching loss of the South Caucasus." While such statements may be premature and alarmist, they nonetheless reflect Moscow’s growing concerns regarding its long-term strategic foothold in the region.

Iran and Russia appear to prioritize a shared geopolitical objective: the de-Westernization of the South Caucasus and the prevention of strengthened U.S. regional influence. This strategic alignment is explicitly reflected in Clause 12 of the Russo-Iranian Treaty, which underscores both parties’ commitment to “strengthening peace and security in the Caspian Sea region, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the Middle East [to] prevent destabilizing interference by third parties” in these areas.

In this context, some experts suggest that Iran’s increased diplomatic involvement in regional affairs is likely. One potential avenue for such engagement is the "3+3" format, which includes Armenia, Iran, Russia, Georgia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan. Initially proposed by Ankara and Baku, the framework has since received active support from Moscow as a means to reduce the risk of Western powers gaining a foothold in the South Caucasus. Iran’s participation in this diplomatic initiative could further consolidate its regional influence while aligning with Russia’s broader strategic objectives.

CONCLUSIONS: The expansion of Russo-Iranian ties is expected to have a notable impact on the South Caucasus and parts of the Caspian Sea region. Azerbaijan's geo-economic and geopolitical significance is likely to increase further, particularly if economic sanctions against Russia remain in place, compelling Moscow to deepen its reliance on alternative regional partners.

Russia, whose regional standing is in decline, might unexpectedly benefit from Iran’s strategic weakening. Given its growing security concerns, Tehran may become more inclined to collaborate with Moscow in the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea region to safeguard its strategic depth and border security.

From a broader strategic perspective, a greater Russian presence in the region should be viewed as a negative development. Given the region’s complexity and history of conflict, Russia’s potential increased involvement—if it materializes—poses a significant risk. Historically, Moscow’s regional policies have regularly contributed to greater instability rather than fostering long-term security, raising concerns about the potential destabilizing consequences of renewed Russian engagement in the South Caucasus and Caspian Sea region.

AUTHOR BIO: Dr. Sergey Sukhankin is a Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation and the Saratoga Foundation (both Washington DC) and a Fellow at the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (Canada). He teaches international business at MacEwan School of Business (Edmonton, Canada). Currently he is a postdoctoral fellow at the Canadian Maritime Security Network (CMSN).

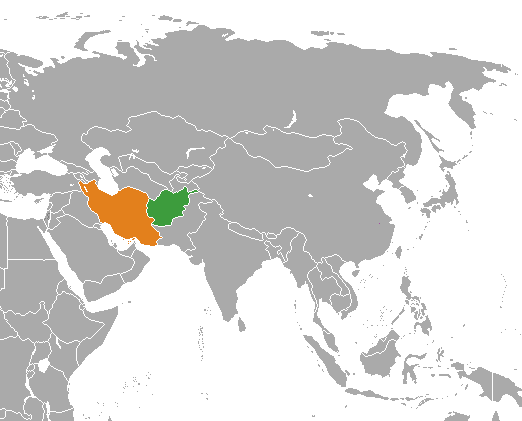

Transport Projects in Afghanistan: Iran's Ambitions and a Balancing Central Asia

By Nargiza Umarova

In recent years, the Taliban government has successfully garnered the support of most Central Asian countries for the development of trans-Afghan transport infrastructure. Notably, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have demonstrated significant engagement in this endeavor, with each country advancing its own railway project traversing Afghanistan to reach the borders of Pakistan. These routes are expected to compete with one another, a dynamic that is anticipated to enhance their profitability through the implementation of flexible tariff policies aimed at maintaining sufficient cargo flow. The establishment of trans-Afghan rail corridors holds strategic significance not only for fostering connectivity between Central and South Asia but also for advancing Iran’s aspirations to develop efficient transportation links with China via Afghanistan—a goal that the Taliban government has expressed its willingness to support.

Photo by Pahari Sahib

BACKGROUND: In May 2023, Afghan authorities approved the Mazar-i-Sharif-Herat-Kandahar railway corridor project, which spans 1,468 kilometers. A year later, plans were announced for the construction of the Spin Boldak-Kandahar railway, signaling the intention to extend the Kandahar route to Pakistan. Turkmenistan promptly capitalized on this development by proposing an alternative version of the Trans-Afghan Corridor, extending along the Torghundi-Herat-Kandahar-Spin Boldak route.

Subsequently, Kazakhstan joined the project at the invitation of Ashgabat, and in September 2024, the foundation was laid for a 22-kilometer railway line connecting the border station of Torghundi to Sanobar. This section will serve as the initial segment of the Torghundi-Herat transport corridor.

The Turkmen version of the trans-Afghan railway is regarded as an alternative to the Kabul Corridor (the Termez-Mazar-i-Sharif-Kabul-Peshawar railway), although the latter route is significantly shorter. Competition between the western route (originating from Turkmenistan's border) and the eastern route (originating from Uzbekistan's border) appears inevitable. However, this competition is expected to yield positive outcomes, particularly through the reduction of transportation costs resulting from the launch of additional trade routes through Afghanistan. This cost efficiency is a critical factor driving the interest of external stakeholders in the development of trans-Afghan transport infrastructure.

The establishment of the Torghundi-Spin Boldak international transport corridor holds particular importance for Tehran, which intends to develop a railway link with Afghanistan through the border town of Zaranj.

Since 2020, as part of the broader development of Iran's deep-sea port of Chabahar, construction has been underway on the Chabahar-Zahedan railway. This railway is planned to extend further into Afghanistan, reaching the provinces of Nimroz and Kandahar. Recently, Afghan authorities announced the completion of engineering surveys for the construction of the Zaranj-Kandahar railway. This integrated infrastructure will provide Iran with an additional avenue to access Afghanistan, while also establishing a direct connection to Herat—one of Afghanistan's largest and most strategically significant cities.

Tehran’s long-term strategic vision positions Herat as a pivotal hub for transit routes connecting Western, Central, and Eastern Asia. This perspective stems from the concept of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Iran railway corridor, commonly referred to as the "Five Nation Road." Iran has already initiated the practical implementation of this vision through the construction of the Khaf-Herat railway, which is scheduled to become operational in 2025. Once completed, the route will extend to Kashgar in China via Central Asia, covering an approximate distance of 2,000 kilometers.

IMPLICATIONS: Iran has consistently encouraged Afghan authorities to collaborate with their Central Asian partners in advancing the railway corridor connecting Khaf to Kashgar.

In 2017, Uzbekistan and Afghanistan reached an agreement to construct the Mazar-i-Sharif-Sheberghan-Maimana-Herat railway. Integrating this new route with the Khaf-Herat railway would enable Uzbekistan to establish an alternative transit corridor to Iran, Turkey, and the Gulf countries, bypassing Turkmenistan. Additionally, this development would have a substantial impact on the implementation of the Five Nation Transit Route, as the Khaf-Herat-Mazar-i-Sharif railway constitutes a critical segment of the Afghan portion of this corridor. From Mazar-i-Sharif, transportation links would only need to be extended to Sherkhan Bandar in Kunduz province to connect with Tajikistan's border.

However, in 2018, Tashkent introduced a new trans-Afghan railway project toward Pakistan, known as the Kabul Corridor, effectively placing the implementation of the Mazar-i-Sharif-Herat route on hold. This decision was likely influenced by the recognition that the railway to Herat could undermine Uzbekistan’s transit interests. By prioritizing the Kabul Corridor, Uzbekistan sought to secure its role in servicing freight flows from China, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan to Iran, Turkey, and Europe.

Despite these developments, progress on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Iran railway corridor continued. In 2019, Afghanistan and Tajikistan signed an agreement to construct the Jaloliddini Balkhi (Kolkhozobod)-Panji Poyon-Sherkhan Bandar railway. To finance the feasibility study for this project, Dushanbe sought assistance from prominent international donor organizations, including the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

At that time, establishing a railway connection between Afghanistan and Tajikistan was also pivotal for the development of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Tajikistan (TAT) transport corridor, initiated in 2013. This corridor extends from the Tajik border into northern Afghanistan, passing through the cities of Kunduz, Khulm, Mazar-i-Sharif, Sheberghan, and Andkhoy. At the Akina checkpoint, the railway crosses into Turkmenistan, from where it can connect to the Caspian Sea. This route aligns with the concept of reviving the ancient Lapis Lazuli Corridor, which aims to provide Afghanistan with direct access to European markets via the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.

In 2016, Turkmenistan completed the first stage of the TAT railway, spanning the Atamurat (Kerki)-Ymamnazar-Akina route. By early 2021, the Akina-Andkhoy railway line also became operational. However, the abrupt change of power in Afghanistan during the summer of 2021 led to the suspension of work on these projects. This pause stemmed from uncertainty regarding the Taliban government's approach to relations with neighboring countries and its foreign policy on transport communications. Yet contrary to initial expectations, the new leadership in Afghanistan adopted a notably more pragmatic stance on these matters.

The Taliban have reactivated nearly all regional and interregional transport projects. Announcements have been made regarding the planned launch of the Andkhoy-Sheberghan and Sheberghan-Mazar-i-Sharif railway lines in the coming years, as well as the construction of the Mazar-i-Sharif-Herat railway. These initiatives aim to bridge critical gaps in major trade corridors, including the TAT and the Five Nation Railway Route.

Notably, even Tajikistan, despite its tough stance toward the Afghan government, has become more active in advancing trans-Afghan transport initiatives. In July 2024, Tajikistan’s Ministry of Transport and the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) signed a protocol to develop a feasibility study for a 51-kilometer Jaloliddini Balkhi-Panji Poyon railway, which will connect to Afghanistan via the Sherkhan Bandar checkpoint. As previously mentioned, this railway will form part of the TAT.

Integration into such international transport corridors will offer Tajikistan a strategic advantage on southern transit routes. However, the modernization of existing infrastructure and the construction of new railways demand significant financial resources, which Dushanbe struggles to provide. Tajikistan relies heavily on China for foreign investment. Beijing has a vested interest in developing fast and efficient transportation routes to access emerging markets in South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

If the Taliban succeed in persuading Tajikistan to collaborate on developing trade routes to China, this could significantly reshape Central Asia's transport architecture while enhancing Afghanistan's strategic importance as a regional transit hub. Iran would also benefit from a direct connection to China that bypasses Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan.

For Tashkent, however, this development could present a serious challenge given the resolve of its neighbors to complete the TAT.

CONCLUSIONS: The proactive efforts of the Taliban government in developing international transport links has heightened the interest of most Central Asian states (with the exception of Tajikistan) in strengthening trade and economic ties with Kabul. This includes the potential implementation of joint investment projects, such as the construction of railways, gas pipelines, and power lines, which could foster regional connectivity and economic growth.

External major powers are also eager to capitalize on these transformations, but their interference in establishing trans-Afghan transport infrastructure could have adverse consequences for Central Asia.

Iran’s ambitions to establish a transport corridor to China via Afghanistan pose the potential to alter the balance of power within the regional transit system. Such a development would bolster the positions of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, which are currently in a transport deadlock and reliance on Uzbekistan for access to global markets.

The development of new trade routes through Afghanistan represents a positive trend that will inevitably influence Central Asia due to the region’s geographical proximity. This shift offers regional states the opportunity to enhance their transit and trade capacities, albeit accompanied by increased competition. To mitigate the risks of intense rivalries, the Central Asian republics must reconcile their interests in light of Afghanistan’s growing significance as a transit hub and formulate a coordinated strategy to advance interregional transport corridors, ensuring equitable benefits across the region.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Nargiza Umarova is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Advanced International Studies (IAIS), University of World Economy and Diplomacy (UWED) and an analyst at the Non-governmental Research Institution “Knowledge Caravan”, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Her research activities are focused on studying developments in Central Asia, trends in regional integration and the influence of big powers on this process. She also explores the current policy of Uzbekistan on the creation and development of international transport corridors. She can be reached at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .

Iran’s Security Posture in the South Caucasus After the War in Ukraine

Ilya Roubanis

June 6, 2024

Iran’s engagement in the South Caucasus needs a new diplomatic taxonomy. The invasion of Ukraine reframes the way Iran, Russia, and Turkey engage with each other to define this region. Conceptually, for Iran the war in Ukraine is an opportunity to transition from the margins of a global rules-based system to the epicentre of a regional status quo as a rules maker rather than a pariah. The key to this new taxonomy is a working relationship with Turkey and Russia, reigning over the ambitions of Azerbaijan, and restricting the scope for Israeli influence. In this scheme, Armenia is an instrumental junior partner of geopolitical but limited geoeconomics significance.

Is the Aras Corridor an Alternative to Zangezur?

By Vali Kaleji

February 5, 2024

Iran and Azerbaijan recently agreed to establish a transit route called the “Aras Corridor.” It is intended to pass through the Iranian province of East Azerbaijan and connect the village of Aghband in the southwestern corner of the Zangilan District to the city of Ordubad in southern Nakhchivan. Bypassing Armenia, the Aras Corridor could present an alternative to the Zangezur Corridor with the potential of reducing Iran’s concerns for its common border with Armenia. However, if Armenia and Azerbaijan sign a peace treaty and Armenia and Turkey establish diplomatic relations, the current advantages of the Aras Corridor will be reduced. These equations will change only if Nikol Pashinyan’s government falls and the nationalist and conservative movements opposing peace with Azerbaijan and normalization of relations with Turkey come to power in Armenia.

Silk Road Paper S. Frederick Starr,

Silk Road Paper S. Frederick Starr,  Book Svante E. Cornell, ed., "

Book Svante E. Cornell, ed., "