The First Phase of the TAPI Gas Pipeline: From Serhetabat, Turkmenistan to Herat, Afghanistan

By Vali Kaleji

The construction of the first phase of the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Gas Pipeline (TAPI) gas pipeline constitutes a key component of the Taliban's broader strategy to revive significant energy transfer and transit projects that were suspended following their return to power. The successful implementation of these initiatives is expected to enhance the internal legitimacy of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. However, unlike the preceding two decades, the leadership of Pakistan and India have not participated in the construction of the first phase of the TAPI gas pipeline. Adopting a pragmatic and incremental approach, the Taliban leadership has chosen to advance this energy transfer project in collaboration with Turkmenistan in a phased manner. It appears that Pakistan and India have cautiously opted to wait and watch regarding their involvement in the TAPI gas pipeline.

BACKGROUND: The transfer of Turkmenistan’s gas resources to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India has faced numerous challenges over the past three decades and remains unimplemented. This initiative has been referred to by various names over time, including “Trans Afghan” (1995), “Consortium of Central Asia Gas Pipeline, CentGas” (1997), “Trans-Afghan Gas Pipeline, TAGP” (2002), and TAPI (2010). These projects proposed the construction of a 1,814 kilometer pipeline to transport natural gas from the Galkynysh gas field in Turkmenistan, the world’s second-largest gas field, through Afghanistan and Pakistan to India. The Afghan section of the pipeline, spanning 816 kilometers, will traverse the provinces of Herat, Farah, Nimroz, Helmand, and Kandahar. The pipeline will enter from Quetta in Balochistan and pass through Dera Ghazi Khan, Multan and Fazilka, a city at Indian border 150 kilometers from Multan. From Fazilka, the pipeline will enter India.

The pipeline was designed with an estimated annual transmission capacity of 33 billion cubic meters (bcm). It will supply 5 percent of the gas to Afghanistan, 47.5 percent to Pakistan, and 47.5 percent to India during its 30-year operational period. Afghanistan will receive 500 million cubic meters of gas for the first decade, 1 bcm in the second decade, and 1.5 bcm in the third decade.

To implement the TAPI pipeline project, Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani, Turkmenistan’s President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and India’s Vice President Hamid Ansari convened in 2015, in Turkmenistan’s remote Karakum Desert, to inaugurate the proposed pipeline. However, the construction was hindered by several factors, including financial constraints, insecurity in Afghanistan, and the terrorist activities of groups such as the Taliban, ISIS, and Al-Qaeda. Additionally, persistent tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as between Pakistan and India, further obstructed the project’s progress.

A decade later, on September 10, 2024, the construction of the Serhetabat-Herat section of TAPI was inaugurated on the border of Turkmenistan and Afghanistan. The ceremony was attended by Turkmenistan’s President Serdar Berdimuhamedov and Chairman of the Halk Maslahaty, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, as well as the Acting Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of Afghanistan, Mullah Mohammed Hasan Akhund.

Unlike the earlier inauguration, the leaders of Pakistan and India were notably absent from this event. The ceremony marked the commencement of TAPI’s first phase, spanning from Serhetabat (formerly Gushgy) in Turkmenistan to Herat in Afghanistan. The subsequent three phases are planned to extend the pipeline from Herat to Helmand, from Helmand to Kandahar, and finally from Kandahar to the Pakistan border.

Adopting a pragmatic and phased approach, the Taliban leadership has chosen to advance the TAPI project in collaboration with Turkmenistan in four distinct stages. This incremental strategy enables the Taliban regime to demonstrate its political resolve, operational capacity, and ability to ensure the security of the project to Turkmenistan, Pakistan, and India.

Over the past two years, the Taliban has achieved significant milestones, including the completion of the first phase of the TAP-500 energy system project (Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan), the inauguration of the Herat Noor-ul-Jihad Substation and Turkmenistan electricity transmission project, the opening of a 177-meter railway bridge on the Serhetabat–Torghundi railway at the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan border, the initiation of the Shatlyk-1 gas compressor station construction at the Shatlyk field in Mary Province, the launch of a fiber-optic communication line along the Serhetabat-Herat route, and the commencement of the 22-kilometer Torghundi-Sanabar railway construction, marking the first segment of the Torghundi-Herat railway.

These accomplishments have likely bolstered the Taliban’s confidence as they proceed with the implementation of the first phase of TAPI.

IMPLICATIONS: The project is a critical element of the Taliban’s broader strategy to revive significant energy transfer and transit projects, including CASA-1000 (the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan electricity transmission line), the Lazorde project (linking Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey), the Chabahar port transit initiative (connecting Afghanistan, Iran, and India), and the Uzbekistan-Afghanistan railway route. These projects, which were suspended following the Taliban's return to power, are expected to generate employment and income for various provinces in Afghanistan, thereby bolstering the Taliban’s domestic legitimacy.

In line with these efforts, the Taliban declared a public holiday in Herat province on September 11, 2024, coinciding with the inauguration of TAPI’s first phase. This move appears to reflect a deliberate effort at public diplomacy or propaganda, aimed at showcasing the Taliban’s commitment to national development and infrastructure revival.

If TAPI becomes operational, it will create jobs for over 12,000 Afghans, and the project could generate approximately US$ 1 billion annually in revenue for the country. This gas supply will be crucial for meeting the energy needs of urban and rural areas, as well as supporting industrial and production centers in densely populated and strategically important regions such as Herat, Helmand, and Kandahar.

Furthermore, the successful implementation of significant energy transfer and transit projects, such as TAPI, holds the potential to strengthen the Taliban’s diplomatic and economic ties with neighboring countries. Such developments are particularly critical for the Taliban leadership, given its international isolation.

An important aspect of the TAPI project is the decision to construct its four phases without reliance on international financial aid. Both Turkmenistan and the Taliban recognize that, given the lack of international recognition of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, securing financial assistance or loans from institutions such as the Asian Development Bank is not feasible. This constraint likely influenced the decision to proceed with the phased implementation of TAPI exclusively within Afghanistan, excluding the active participation of India and Pakistan at this stage.

The construction and operation of the pipeline are overseen by TAPI Pipeline Company Limited (TPCL), based in Dubai. TPCL is a joint venture between Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India, with each country holding a stake in the project. The state-owned company Turkmen Gas holds a dominant 85 percent share in TPCL, while the remaining 15 percent is equally distributed among Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Consequently, it is anticipated that TPCL will finance the construction of the four phases of the TAPI pipeline within Afghanistan.

Should the pipeline be extended to Pakistan and India, the financing strategy would likely involve not only allocating the respective shares of Pakistan and India from TPCL but also securing additional funding through financial institutions such as the Asian Development Bank to support the broader extension.

Another significant implication of TAPI, even if limited to its four phases within Afghanistan, is the increased diversification of Turkmenistan’s gas export destinations and routes. Over the past three decades, Turkmenistan has developed gas export pipelines along three primary routes: northern (Russia), eastern (China), and western (Iran and Turkey). The implementation of TAPI would establish a new southern route, enhancing Turkmenistan’s gas export network. This diversification is expected to strengthen Turkmenistan’s position in the regional gas market, providing the country with greater leverage and bargaining power in negotiations.

Additionally, Turkmenistan remains attentive to the dynamics of its competitors, particularly Iran. International sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council in the past, along with unilateral sanctions by the U.S. in recent years, have significantly curtailed Iran’s foreign investment, production, and export capacity. These sanctions have also stalled major gas transmission initiatives, most notably the Peace Pipeline (Iran-Pakistan-India). In this context, the successful implementation of TAPI could position Turkmenistan as a more reliable and influential player in the regional energy market, capitalizing on opportunities that competitors like Iran have been unable to pursue.

However, Turkmenistan will need to secure additional foreign investment to expand its gas production capacity to ensure a sustainable supply for its growing base of gas-consuming customers. The country’s ability to meet this challenge will be crucial as it seeks to maintain its role as a reliable energy supplier in an increasingly competitive regional and global market.

This challenge will become even more pronounced if Turkmenistan succeeds in implementing the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline project in collaboration with Azerbaijan, Turkey, and the European Union. Such a project, aimed at supplying gas to European markets, would further strain Turkmenistan’s production capacity. The increased demand would necessitate significant investments in infrastructure and technology to scale production while ensuring the reliability and sustainability of its gas exports across multiple routes and to diverse markets.

CONCLUSIONS: The full implementation of TAPI will hinge on several critical factors. These include the political will of the leaders of the four participating countries—Turkmenistan, Afghanistan under Taliban leadership, Pakistan, and India—along with the ability to ensure security throughout all stages of construction and operation. Particular attention must be given to mitigating threats from groups such as ISIS and Al-Qaeda. Additionally, effective operation and distribution of gas through rural and urban areas, as well as the mobilization of the substantial financial resources required for this ambitious project (estimated at US$ 7 to 8 billion), are essential for its success.

Moreover, the project must remain insulated from the complex and often contentious disputes between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India. The successful completion of the current four phases of TAPI is seen as a critical test for the Taliban-led Islamic Emirate in demonstrating its capability to execute such a significant energy transfer initiative after three decades of delay.

Pakistan and India are seemingly opting to wait and watch to assess the feasibility and progress of the project under the Taliban’s stewardship. Should the Taliban successfully implement these initial phases, Pakistan and India can be anticipated to join efforts to extend the project further.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Vali Kaleji, based in Tehran, Iran, holds a Ph.D. in Regional Studies, Central Asian and Caucasian Studies. He has published numerous analytical articles on Eurasian issues for the Eurasia Daily Monitor, the Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, The Middle East Institute and the Valdai Club. He can be reached at

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

.

India, Pakistan, and the South Caucasus Arms Race

By Syed Fazl-e-Haider

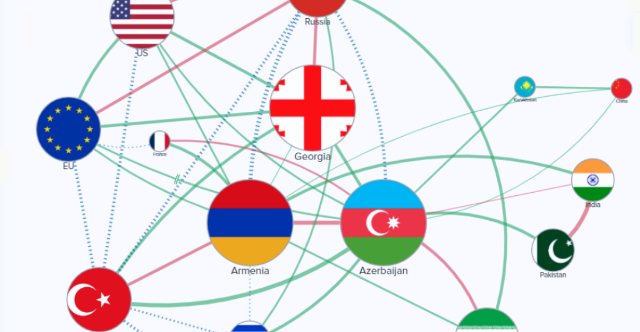

Pakistan and India, the longstanding rivals in South Asia, have instigated an arms race in the South Caucasus region. This development comes amid a broader arms supply deficit caused by Russia's preoccupation with the ongoing conflict in Ukraine. While India is deepening its military partnership with Armenia, Pakistan is enhancing the defense capabilities of Azerbaijan. Both states are actively seeking to fill the vacuum in arms procurement left by Russia's reduced presence in the region. India has aligned with Armenia, leveraging this partnership to pursue strategic connectivity projects in the South Caucasus. Conversely, Pakistan views Azerbaijan as a strategic ally, with their collaboration deemed essential for countering India in the competition for regional influence.

BCKGROUND: India and Pakistan have shared a contentious relationship since their emergence as independent states in 1947. The two states have engaged in three full-scale wars, primarily over Kashmir, a territory claimed by both. In 1998, Pakistan conducted nuclear tests shortly after India, marking a significant escalation in their rivalry. This ongoing antagonism often manifests in international forums, where the two countries accuse each other of fostering cross-border terrorism. Their rivalry extended to the South Caucasus in 2020, during the 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region.

Pakistan supported Azerbaijan during the Second Karabakh War in 2020. However, the close relationship between the two countries predates this conflict, with their cordial ties dating back to Azerbaijan's independence in 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Pakistan was among the first nations to recognize Azerbaijan's independence, second only to Türkiye. After Armenian forces attacked Azerbaijan's Nagorno-Karabakh region shortly after its independence, both Türkiye and Pakistan strongly condemned Armenia's actions. Since then, they have consistently supported Azerbaijan’s position on the Nagorno-Karabakh issue in international forums, both politically and diplomatically. Pakistan has gone so far as to refrain from recognizing Armenia, refusing to establish diplomatic relations with the country. In return, Azerbaijan has endorsed Pakistan’s stance on the Kashmir dispute, a position that has antagonized India.

During the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Islamabad was alleged to have sent military advisers to support Azerbaijan. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan even claimed that Pakistani soldiers were actively fighting alongside the Azerbaijani army against Armenia during the 44-day conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh. Pakistan, however, categorically dismissed these allegations, labeling them as "baseless and unwarranted." Ultimately, Azerbaijan emerged victorious in the six-week war over the disputed region.

Türkiye strongly backed Pakistan's position on Kashmir, reciprocating Pakistan’s unequivocal support for Azerbaijan during the Karabakh war. The mutual endorsements of Islamabad's stance on Kashmir by Ankara and Baku provoked concern in New Delhi. Pakistan’s support for Azerbaijan during the conflict played a pivotal role in fostering closer ties between India and Armenia in the aftermath of the war. Observing its rival’s activities during the Karabakh conflict, India responded by significantly enhancing its defense partnership with Armenia over the subsequent four years.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, and Türkiye formalized their alliance by signing the Trilateral Islamabad Declaration in 2021, underscoring their solidarity with Azerbaijan in the aftermath of the war.

IMPLICATIONS: The supply of military equipment by India and Pakistan has significantly reduced Azerbaijan's and Armenia's dependence on Russia for weapons and ammunition. Historically, both South Caucasian nations relied heavily on Russia for defense supplies, particularly in the period preceding the 2020 Karabakh War. Between 2011 and 2020, Russia accounted for 94 percent of Armenia's major arms imports, including armored personnel carriers, air defense systems, multiple rocket launchers, and tanks. Similarly, Azerbaijan depended extensively on Russian military supplies during the same period, purchasing armored vehicles, air defense systems, Smerch rockets, transport and combat helicopters, artillery, multiple rocket launchers, and tanks.

India considers Armenia a strategic partner in the South Caucasus and has consequently deepened its military ties with Yerevan. Armenia has emerged as the largest foreign recipient of Indian weapons, with defense contracts concluded since 2020 estimated at US$ 2 billion. According to a report by the Indian Ministry of Finance, Armenia has become the leading importer of Indian arms, securing deals for the purchase of Pinaka multiple-launch rocket systems and Akash anti-aircraft systems. This development reflects a significant realignment in the defense landscape of the region.

In September, Azerbaijan formally introduced Pakistan’s fourth-generation JF-17 Thunder Block III fighter jets to its air force, marking a significant milestone in defense cooperation between the two nations. This development followed a US$ 1.6 billion agreement signed in February for the acquisition of JF-17 Block III aircraft. The deal includes not only the supply of aircraft but also ammunition and pilot training provided by Pakistan. The advanced combat capabilities of the JF-17 Block III are expected to enhance Azerbaijan's military edge in the South Caucasus. Notably, Azerbaijan has requested 60 JF-17 jets, intended to replace its entire fleet of aircraft, making this the largest defense export deal in Pakistan’s history.

The defense agreements between India and Armenia, as well as those between Pakistan and Azerbaijan, have significantly diminished Russia’s position as the principal supplier of weapons and ammunition to the South Caucasian nations. This shift has been exacerbated by Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, which has undermined its ability to deliver weapons in a timely manner under previously signed contracts. The entry of India and Pakistan into the regional defense market has provided Armenia and Azerbaijan with an opportunity to diversify their military procurement, reducing their historical reliance on Russian defense supplies.

The entry of India and Pakistan into the South Caucasus has resulted in the formation of two rival blocs competing for regional influence. One alliance, referred to as the Three Brothers, comprises Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and Pakistan, while the opposing group includes Armenia, Iran, France, and India.

For India, Armenia holds strategic importance as a potential bridge to access the vast market of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). New Delhi views Armenia as a vital transit hub for connecting Indian goods to EU countries and envisions its role in facilitating bilateral or multilateral partnerships with nations such as Iran, France, and Greece to implement strategic connectivity projects in the South Caucasus.

Conversely, Islamabad considers its partnership with Azerbaijan critical for countering India's influence in the region. Azerbaijan has also emerged as a key player in the energy transit corridors connecting the Black Sea, South Caucasus, and Europe, further enhancing its geopolitical significance. This dynamic positions Azerbaijan as a strategic ally for Pakistan, particularly in the context of their shared interests in limiting India's regional ambitions.

CONCLUSIONS: Pakistan's defense cooperation with Azerbaijan and India's arms sales to Armenia are shaping new security dynamics that link the South Caucasus and South Asia. The extensive defense contracts between India and Armenia are poised to strengthen Armenia's position as a strategic ally for India in the region.

India's military partnership with Armenia is influenced by its geopolitical rivalry with Pakistan, which is actively supporting Azerbaijan's defense capabilities. Both Pakistan and India aim to secure reciprocal cooperation from the South Caucasian nations to advance their strategic interests. For Pakistan, Azerbaijan holds particular importance as a potential partner in trans-regional energy cooperation, given Pakistan's energy deficiencies. Azerbaijan's pivotal role in the energy transit corridor connecting South Asia and the South Caucasus further underscores this strategic alignment.

Conversely, India, as an observer in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), is working to deepen its cooperation with Armenia across economic sectors, with a particular emphasis on defense. Armenia's strategic position could also facilitate India's broader connectivity initiatives with Europe. Meanwhile, Pakistan is likely to leverage its relationship with Azerbaijan to counterbalance India's growing influence in the region, highlighting the interconnected and competitive geopolitical landscape of the South Caucasus and South Asia.

AUTHOR’S BIO: Syed Fazl-e-Haider is a Karachi-based analyst of the Wikistrat. He is a freelance columnist and the author of several books. He has contributed articles and analysis to a range of publications. He is a regular contributor to Eurasia Daily Monitor of Jamestown Foundation.

Will the Shanghai Cooperation Organization Reconfigure Educational Cooperation?

WILL THE SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION RECONFIGURE REGIONAL EDUCATIONAL COOPERATION?

By Rafis Abazov

The recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Astana has rekindled discussions on the role of the organization in reshaping regional educational cooperation. Historically known for its focus on security and economic issues, the SCO is increasingly recognizing education as a cornerstone for sustainable development and regional stability. This shift is significant for member states—China, Russia, India, and several Central Asian countries—as they navigate the complexities of globalization and seek to bolster their human capital. The main question is whether declarations at the summit denote a shift in the regional educational architecture.

BACKGROUND: Since its inception in 2001, the SCO has primarily concentrated on security cooperation and economic integration among its member states. However, the need for a skilled workforce, capable of driving innovation and economic growth, has brought education into the spotlight. The Astana SCO-2024 Summit underscored this shift, highlighting the potential of educational cooperation to foster mutual understanding, enhance economic ties, and promote cultural exchanges. In recent years, the SCO has launched various educational initiatives. The establishment of the SCO University Network, the SCO Youth Council and regional scholarship themes led to a sharp increase in regional student mobility – for example China reached a milestone in 2022 by attracting one million foreign students, while Kazakhstan attracted almost 30,000. Indeed, these efforts facilitated academic exchanges, joint research projects, and cultural interactions among students and scholars from member countries. The Astana summit built on these foundations, proposing a more structured and collaborative approach to educational cooperation, as almost one quarter of the 31 agreements signed during the summit were dedicated to the area of science and education. On top of this, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education hosted the regional conference “Cooperation in the field of higher education and production integration,” focused on developing a unified approach to accreditation, curriculum design, quality assurance, student mobility and mutual recognition of qualifications.

IMPLICATIONS: One of the important areas discussed at the Astana summit was the enhancement of academic exchanges and research collaborations. By fostering partnerships between universities and research institutions across member states, the SCO aims to create a robust network of knowledge and innovation. Such collaborations can lead to significant breakthroughs in various fields, from science and IT technology to social sciences and smart agriculture.

The proposed initiatives include exchange programs for students and faculty, joint research projects, and the creation of cross-border academic networks and joint research labs to study the impact of climate change at the regional and sub-regional levels. These efforts are expected to enhance the quality of education and research in member states, making them more competitive on the global stage. Another critical focus is the harmonization of educational standards across SCO countries. This alignment would not only enhance educational opportunities but also support a more integrated approach to developing double diploma programs between universities.

The summit proposed the creation of a common framework for higher education within the SCO. This framework would include standardized guidelines for curriculum development, accreditation processes, and quality assurance mechanisms. Such harmonization can make it easier for students to transfer credits between institutions in different countries and for professionals to have their qualifications recognized across the region. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of digital education and technological integration.

The SCO members acknowledged that there is a rapid shift towards online learning, and an urgent need to invest in digital infrastructure and resources. The Astana summit highlighted the potential for collaboration in developing e-learning platforms, distance education programs, and digital literacy initiatives. In this context, the leading Chinese universities (such as Chinese Agriculture University) took initiatives to exploring ways of leveraging technology to bridge the digital divide among member states by promoting access to quality education and facilitating lifelong learning and upskilling, essential for adapting to the rapidly changing job market.

The creation of cohesive and inclusive frameworks would help to upscale the internationalization of education by integrating educational systems, and organizational cultures across SCO member states, and developing joint digital infrastructure. However, these initiatives require significant investments. Indeed, economic disparities among member states pose significant challenges. While some countries have advanced educational and digital infrastructures, others may struggle with limited resources and capacity. At least three countries – China, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan – have allocated significant resources for bridging this gap, supporting deeper educational collaboration, and accelerating the adoption of online learning, access to digital tools and other resources.

CONCLUSION: The Astana summit SCO-2024 has set the stage for the SCO to play a transformative role in regional educational cooperation. As member states work to align their educational systems and policies, the organization is poised to reshape the regional educational architecture significantly. With a focus on academic collaboration, standardization, and digital innovation, the SCO is on a path to create a more integrated and dynamic educational ecosystem.

The success of future initiatives will depend on building on the foundations laid by existing programs. Strengthening and expanding platforms like the SCO University Network, the SCO Youth Council and numerous educational consortiums can provide a solid base for more ambitious projects. These platforms can serve as hubs for collaboration, innovation, and cultural exchange. Effective implementation requires the active engagement of various stakeholders, including governments, educational institutions, the private sector, and civil society. Collaborative efforts and partnerships can ensure that initiatives are well-designed, adequately funded, and effectively implemented.

The SCO has the potential to reconfigure regional educational architecture by enhancing educational cooperation and recognizing education as a cornerstone for regional development and peaceful integration. The outcomes of the Astana meeting signal a promising future for educational collaboration in the SCO region, with the potential to yield significant economic, social, and cultural benefits. As the SCO continues to evolve, its focus on education can play a transformative role in shaping the region’s future. By fostering a more interconnected and innovative educational landscape, the SCO can contribute to a more prosperous, stable, and cohesive region.

The Astana summit has marked a new chapter in this journey, setting the stage for the SCO to reconfigure the regional educational architecture in meaningful and impactful ways. Joint research projects and academic exchanges can generate new ideas, technologies, and solutions to common problems. This, in turn, can drive economic growth and increase competitiveness, positioning the SCO region as a leader in various fields.

AUTHOR’S BIOS: Rafis Abazov, PhD, is a director of the Institute for Green and Sustainable Development at Kazakh National Agrarian Research University. He is author of The Culture and Customs of the Central Asian Republics (2007), The Stories of the Great Steppe (2013) and some others. He has been an executive manager for the Global Hub of the United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI) on Sustainability in Kazakhstan since 2014 and participated at the International Model UN New Silk Way conference in Afghanistan.

India-Pakistan Strategic Rivalry Extends to the South Caucasus

By Vali Kaleji

March 28, 2024

The development of military and defense relations between Azerbaijan and Pakistan and Armenia and India is an important consequence of the political arrangement and the balance of forces after the Second Karabakh War. However, Pakistan’s non-recognition of Israel has prevented Baku from forming a “quadruple alliance” with its three strategic allies, including Turkey, Israel and Pakistan. Armenia, after defeat in the war and amid dissatisfaction with its traditional ally Russia and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), views India, France and Iran as new strategic options, however, Iran prefers Armenia to maintain its traditional and strategic relations with Russia. The tripartite cooperation between Armenia, Iran and India focus efforts on “soft balancing” (economic-transit) instead of “hard balancing” (military-security), against the tripartite ties of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Pakistan in the South Caucasus.

India’s Changing Approach towards Central Asia and the Caucasus after the Afghanistan Debacle

India’s Changing Approach towards Central Asia and the Caucasus after the Afghanistan Debacle

By: Gulshan Sachdeva

India’s ambition to raise its profile and connect with Central Asian neighbourhood was reflected through its ‘Extended Neighbourhood’ and ‘Connect Central Asia’ policies. Prime Minister Modi further elevated these policies through India’s SCO membership and other institutional mechanisms. India’s strategy towards the region has been linked to its Afghanistan, China and Pakistan policies as well as Russian and U.S. designs. With the Afghanistan debacle, the earlier connectivity strategies are no longer valid as a Taliban-Pakistan-China axis will further strengthen the BRI profile, in which India has not participated. In coming years, New Delhi will work with Central Asian partners to safeguard the region from negative repercussions of the Taliban takeover in terms of radicalization, increased terrorist activity and drug trafficking.

Central Asia and the Caucasus have long been part of the Indian imagination because of old civiliza-tional linkages and cultural connections. After the Soviet break-up, new geopolitical realities and geo-economic opportunities further influenced Indian thinking in the 1990s. The emergence of new independent states opened opportunities for energy imports as well as trade and transit. There were also worries of rising religious fundamental-ism. Therefore, developing political, economic and energy partnerships dominated New Delhi’s “ex-tended neighbourhood” policy in the 1990s. Alt-hough India established close political ties with all countries in the region, economic ties remained limited. An unstable Afghanistan and difficult India-Pakistan relations created problems for di-rect connectivity. New Delhi tried to resolve the issue through working with Russia and Iran via the International North-South Trade Corridor (IN-STC) and its tributaries. Due to the U.S.-Iran ten-sions and stagnating India-Russia trade, this op-tion did not prove very effective. In the mean-while, the Chinese profile in the region increased significantly.

Silk Road Paper S. Frederick Starr,

Silk Road Paper S. Frederick Starr,  Book Svante E. Cornell, ed., "

Book Svante E. Cornell, ed., "